On the Impossibility of Defining a Sandwich: A Formal Investigation

Abstract

The concept of “sandwich” resists formal definition. This paper surveys several attempts to provide necessary and sufficient conditions for the category, including naive structural definitions, geometric classification schemes, legal and regulatory stipulations, topological invariants, and category-theoretic frameworks, and demonstrates that each fails to simultaneously satisfy completeness, consistency, continuity, and alignment with human intuition. We identify the sorites paradox as the underlying obstacle, propose a continuous sandwichness function as the least unsatisfying alternative, and draw a structural analogy to Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. The main result (Theorem 11.1) proves that no definition of “sandwich” can be simultaneously complete, consistent, continuous, and intuitively aligned. The argument has implications for the general problem of natural kind classification under vagueness.

1. Introduction

The question “what is a sandwich?” appears trivial. The prototypical sandwich, sliced bread enclosing a filling, is universally recognizable. Yet every attempt to formalize this intuition produces a definition that either over-generates (admitting items no reasonable speaker would call a sandwich) or under-generates (excluding items that clearly are sandwiches). This difficulty is not unique to sandwiches; it reflects a deep tension between discrete linguistic categories and the continuous variation of the physical world [1].

The sandwich classification problem has received attention in legal [2], culinary [3], and popular scientific [4] contexts, but has not, to the author’s knowledge, been subjected to a unified formal analysis. This paper aims to fill that gap.

We proceed as follows. Section 2 examines and refutes the naive definition. Section 3 introduces a structural formalization. Section 4 surveys the Cube Rule geometric classification. Section 5 reviews relevant legal precedent. Section 6 applies topological methods. Section 7 attempts a category-theoretic approach. Section 8 identifies the underlying sorites structure. Section 9 proposes a continuous alternative. Section 10 draws an analogy to formal incompleteness. Section 11 states and proves the main impossibility result. Section 12 concludes.

2. The Naive Definition

The most commonly offered definition is the following:

Definition 2.1 (Naive). A sandwich is a food item consisting of a filling placed between two pieces of bread.

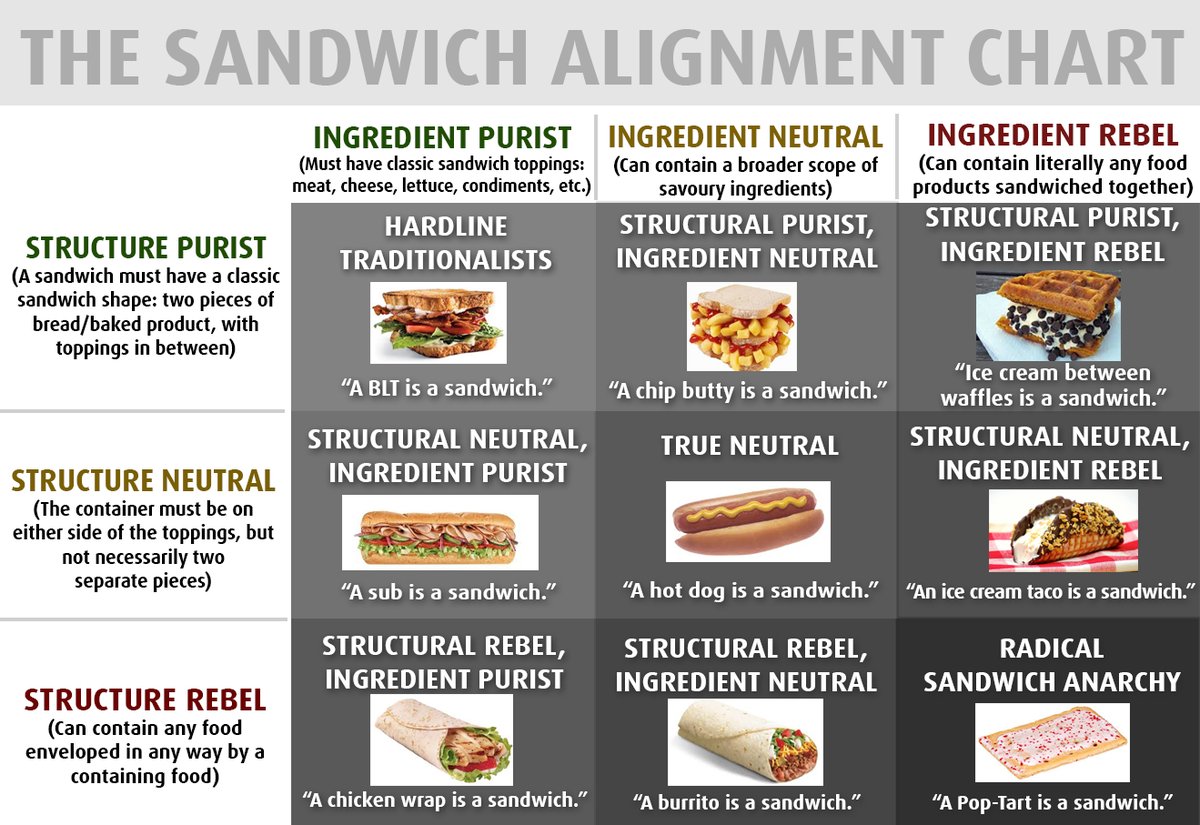

Definition 2.1 is immediately refuted by three well-known counterexamples. The range of positions one might hold is illustrated by the Sandwich Alignment Chart (Figure 1).

Counterexample 2.2 (Open-faced sandwich). The Danish smørrebrød consists of a single slice of bread topped with various ingredients [5]. It is universally referred to as an “open-faced sandwich,” yet it possesses only one piece of bread, violating Definition 2.1.

Counterexample 2.3 (Wrap). A flour tortilla enclosing fillings constitutes a single continuous starch layer with no top-bottom distinction. Major restaurant chains classify wraps as sandwiches for commercial purposes [6], yet they fail the two-piece requirement.

Counterexample 2.4 (Hot dog). A frankfurter in a split bun occupies an indeterminate position (Figure 2). If the bun hinge remains intact, the starch component is a single piece; if it tears, it becomes two pieces. The classification of the item should not depend on incidental structural failure during consumption.

These counterexamples demonstrate that Definition 2.1 is neither necessary (counterexample 2.2) nor sufficient (one can construct non-sandwich items satisfying it, e.g., two slices of bread enclosing a cell phone) for sandwich membership.

3. Structural Formalization

To address the shortcomings of the naive definition, we introduce a structural representation. Let any food item be represented as a tuple:

where denotes the set of components (individual ingredients), denotes the subset of starch-based enclosing elements, and describes the spatial arrangement of relative to .

A candidate formal definition is then:

This definition requires at least one starch element, that the starch elements enclose the non-starch components, and that every element of is indeed starch-based.

The improvement over Definition 2.1 is modest. The critical predicate is undefined and absorbs the full difficulty of the original problem. Whether a taco “encloses” its filling is precisely the kind of boundary question we seek to resolve; delegating it to an unspecified predicate constitutes definitional circularity.

4. The Cube Rule of Food

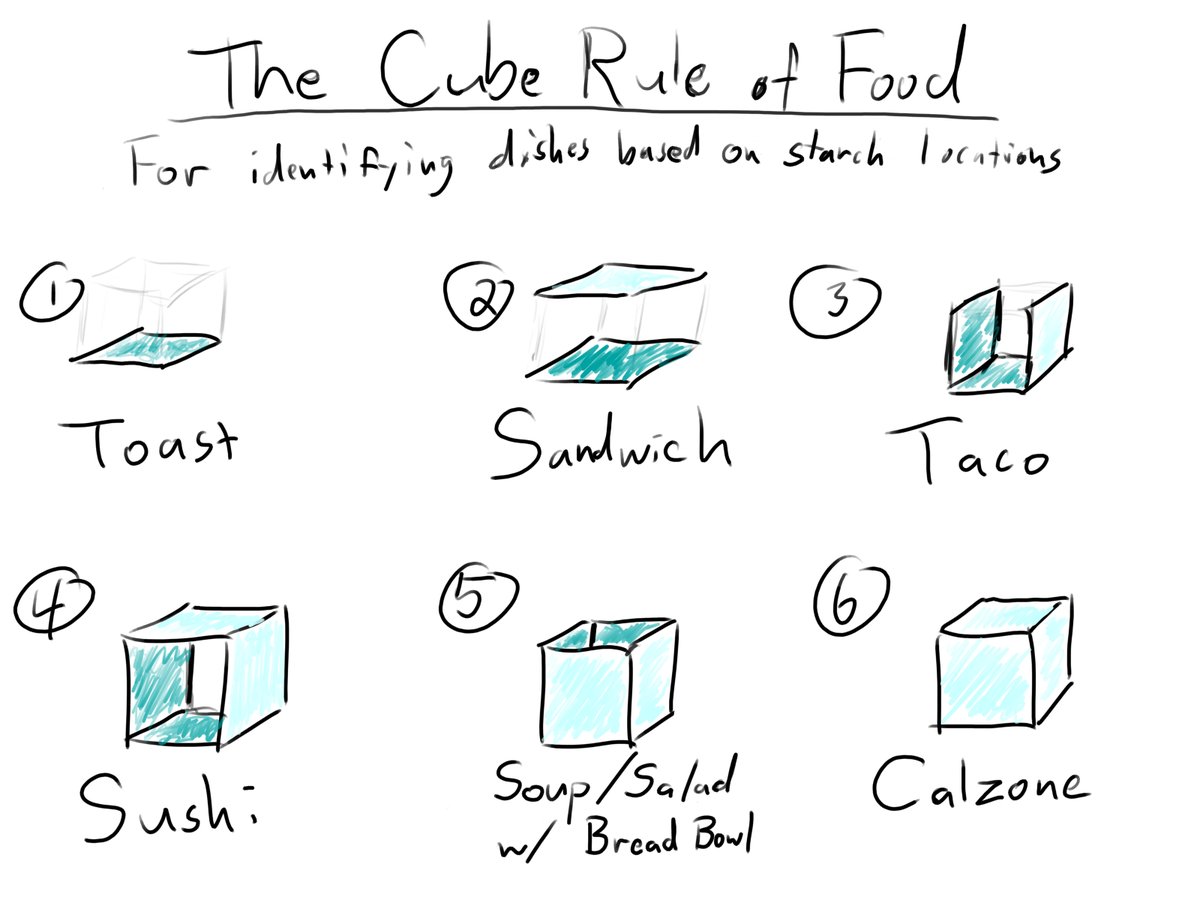

The Cube Rule of Food Identification, proposed by @Phosphatide in 2018 [4], offers a geometric classification scheme. The method models any food item as a rectangular solid with six faces. Each face is classified as starch-bearing or non-starch-bearing, yielding possible configurations. The non-degenerate configurations reduce to six archetypes (see also Figure 3):

| Starch Configuration | Category | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bottom face only | Toast | Pizza, bruschetta, nigiri |

| Top and bottom faces | Sandwich | Club sandwich, Oreo, lasagna |

| Bottom and two lateral faces | Taco | Hard taco, slice of pie |

| Bottom, top, and two lateral faces | Sushi | Burrito, wrap, enchilada |

| All faces except top | Bowl | Bread bowl, pie |

| All six faces | Calzone | Calzone, dumpling, Hot Pocket |

The Cube Rule has the virtue of providing a complete classification: every food item receives a category. However, it reveals a deeper problem. The boundaries between categories are not discrete but continuous.

A burrito with a torn tortilla migrates from “sushi” toward “taco.” A sandwich with pressed edges approaches “calzone.” This suggests that a continuous representation is more appropriate. We define the starch configuration vector:

where each component represents the degree of starch coverage on a given face of the food cuboid. A traditional sandwich corresponds to ; a burrito to .

No natural partition of separates the “sandwich” region from its complement. Any chosen boundary is necessarily arbitrary, as the space admits no topological discontinuity at the proposed classification thresholds.

5. Legal Precedent

Judicial and regulatory bodies have attempted to resolve the sandwich question by definitional fiat.

In White City Shopping Ctr., LP v. PR Restaurants, LLC (2006), the Superior Court of Massachusetts was asked to determine whether a burrito constitutes a sandwich for the purposes of a commercial lease exclusivity clause [2]. The court held that a burrito is not a sandwich, relying on common usage and culinary tradition rather than structural criteria.

The United States Department of Agriculture defines a sandwich as “a meat or poultry filling between two slices of bread, a bun, or a biscuit” [7]. Under this regulatory definition:

- A peanut butter and jelly sandwich is not a sandwich (no meat or poultry component)

- A single folded slice of bread over turkey is not a sandwich (one piece of bread)

- An ice cream sandwich is not a sandwich (no meat or poultry component)

Legal and regulatory definitions resolve the classification problem for their specific jurisdictional purposes, but they do so by stipulation rather than by identifying structural properties. They are therefore unsuitable as general definitions, as they vary across jurisdictions and fail to capture the concept’s extension across culinary contexts [8].

6. Topological Approach

The preceding sections attempted definitions based on structure (Section 3), geometry (Section 4), and legal stipulation (Section 5). Each failed. We now turn to more abstract mathematical frameworks, beginning with topology, which offers a shape-invariant classification method. We define the genus of a food item’s starch component:

- : Genus zero (topologically a sphere). Examples: calzone, dumpling, unsliced bread roll.

- : Genus one (topologically a torus). Examples: bagel sandwich, donut.

- : Genus two. No common food example is known to the author.

Under this classification, a traditional sandwich composed of two disconnected bread slices has a different topological character than a sub sandwich composed of a single hinged roll (). Yet both are uncontroversially sandwiches.

More critically, the topological approach classifies by shape rather than by “sandwichness.” A calzone and an uncut bread loaf share genus zero. No speaker of English considers an uncut bread loaf to be a sandwich. Topological genus is therefore neither necessary nor sufficient for sandwich membership [9].

7. Category-Theoretic Approach

If geometric and topological properties fail to distinguish sandwiches, perhaps algebraic structure can. Define a category whose objects are sandwiches and whose morphisms are sandwich-preserving transformations (operations such as adding a topping, removing a layer, or substituting one bread type for another) that map sandwiches to sandwiches.

The category must satisfy:

- Identity. For every sandwich , the identity morphism exists.

- Composition. For morphisms and , the composite exists.

- Associativity. Composition of morphisms is associative.

This construction is well-defined but circular: the objects of presuppose the very classification we seek to establish [10].

To avoid circularity, consider instead a functor from the category of all food items to a Boolean category:

where is the discrete category with two objects. The functor assigns each food item to either “sandwich” or “not-sandwich.” However, the definition of requires specifying its action on every object of , which is precisely the original classification problem restated in categorical language. The abstraction provides no additional discriminatory power [10].

8. The Sorites Structure

The preceding failures share a common structure: the sorites paradox [11]. In its classical form:

- A collection of 10,000 grains of sand constitutes a heap.

- Removing one grain from a heap yields a heap.

- By induction, a single grain of sand constitutes a heap.

The sandwich analogue proceeds as follows:

- A club sandwich is a sandwich.

- A sufficiently small modification to a sandwich yields a sandwich.

- Therefore, by iterated small modifications, a pizza is a sandwich.

(The sequence: club sandwich flatbread sandwich open flatbread flatbread with tomato sauce flatbread with tomato sauce and cheese pizza.)

We formalize this by defining a metric on the space of all food items:

where quantifies the dissimilarity between two food items. The sorites structure implies:

That is, for any arbitrarily small distance , there exist two food items separated by less than that receive opposite classifications. The classification function is therefore nowhere continuous at the boundary, a necessary consequence of imposing a discrete partition on a connected space [12].

9. The Sandwich Space

The discontinuity identified in Section 8 motivates a continuous alternative.

Definition 9.1 (Sandwichness function). The sandwichness function is defined as:

where represents the degree to which food item exhibits sandwich-characteristic properties. This formulation replaces the binary classification with a fuzzy membership value [13].

The following table provides illustrative (not empirically derived) assignments under this model, intended to convey the qualitative behavior of rather than to assert precise numerical values:

| Food Item | Justification | |

|---|---|---|

| Club sandwich | Prototypical exemplar | |

| Wrap | Single continuous starch layer | |

| Hot dog | Split-bun enclosure | |

| Taco | Partial lateral enclosure | |

| Pizza | Single starch base, no enclosure | |

| Soup | No starch enclosure component |

The sandwichness function eliminates the discontinuity problem by construction. The cost is the loss of a binary decision procedure: provides no threshold above which an item “is” a sandwich. The specific numerical assignments are necessarily subjective, reflecting the prototype-theoretic structure of the concept itself [14].

10. Incompleteness Analogy

We note a structural analogy to Gödel’s incompleteness theorems [15]. Consider a formal system sufficiently expressive to encode statements about food classification. By a diagonal argument analogous to Gödel’s construction, there exist food items such that:

” is a sandwich if and only if cannot prove that is a sandwich.”

Such items are undecidable within , not due to insufficient information, but due to the inherent limitations of the formal system. Any consistent formal classification system for sandwiches must therefore be either:

- Incomplete: there exist food items it cannot classify,

- Inconsistent: it assigns contradictory classifications to some item, or

- Trivial: it classifies all items identically.

While this analogy is informal (culinary taxonomy does not satisfy the arithmetic preconditions of Gödel’s theorems), it captures the essential tension: no non-trivial consistent system can classify all food items [15, 16].

11. Main Result

We now state the central theorem.

Theorem 11.1 (Impossibility of Sandwich Definition). There exists no definition of “sandwich” that simultaneously satisfies:

- Completeness: classifies every food item as either a sandwich or not a sandwich.

- Consistency: never assigns contradictory classifications.

- Continuity: for any , there exists such that implies .

- Intuitive alignment: agrees with the majority of competent English speakers on prototypical cases.

Proof sketch. Properties (1) and (2) together require a total function . Property (3) requires that be continuous. The food space , equipped with the metric from Section 8, is connected (since any two food items can be linked by a continuous path of incremental modifications). But a continuous function from a connected space to (with the discrete topology) must be constant [9, Theorem 23.5]. A constant function either classifies all items as sandwiches or no items as sandwiches, violating property (4).

Corollary 11.2. Any practical sandwich definition must sacrifice at least one of completeness, consistency, continuity, or intuitive alignment.

12. Conclusion

The concept of “sandwich” is best understood not as a classical category defined by necessary and sufficient conditions, but as a family resemblance concept in the sense of Wittgenstein [1]: a cluster of overlapping properties (bread-like enclosure, portability, filling-starch structure, culinary intent) none of which is individually necessary and no combination of which is jointly sufficient.

This result is not specific to sandwiches. Any natural language category applied to continuously varying phenomena will exhibit the same impossibility. The sandwich merely provides a particularly vivid (and gastronomically compelling) instance of a general phenomenon in the philosophy of classification.

References

[1] L. Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, translated by G. E. M. Anscombe, Blackwell, 1953. See particularly sections 66-67 on family resemblance.

[2] White City Shopping Center, LP v. PR Restaurants, LLC, 21 Mass. L. Rptr. 565 (Mass. Super. Ct. 2006).

[3] B. Wilson, Sandwich: A Global History, Reaktion Books, 2010.

[4] @Phosphatide, “The Cube Rule of Food,” cuberule.com, 2018.

[5] H. Notaker, A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page over Seven Centuries, University of California Press, 2017.

[6] Subway Restaurants, “Menu: Wraps,” subway.com, accessed 2026.

[7] United States Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service, 9 CFR 317.

[8] M. Nestle, Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health, 10th Anniversary Ed., University of California Press, 2013.

[9] J. R. Munkres, Topology, 2nd ed., Pearson, 2000.

[10] S. Mac Lane, Categories for the Working Mathematician, 2nd ed., Springer, 1998.

[11] D. Hyde and D. Raffman, “Sorites Paradox,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2018 Edition.

[12] N. J. J. Smith, “Vagueness as Closeness,” Australasian Journal of Philosophy, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 157-183, 2005.

[13] L. A. Zadeh, “Fuzzy Sets,” Information and Control, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 338-353, 1965.

[14] E. Rosch, “Natural Categories,” Cognitive Psychology, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 328-350, 1973.

[15] K. Gödel, “Über formal unentscheidbare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme I,” Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik, vol. 38, pp. 173-198, 1931.

[16] R. M. Smullyan, Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, Oxford University Press, 1992.